Understanding College Equity and Access for First-Generation Students

Jaida Harris

May 6, 2018

Executive Summary

College access programs intentionally operate to combat the issue of inequity within the college matriculation pipeline. Many of these programs are targeted towards first-generation students because these students are often underserved and possess limited access to postsecondary education. These programs are aimed at first-generation students because financial status/class, race, gender, and cultural knowledge are enormous barriers to accessing a postsecondary education. Though the group may be extremely diverse, often first-generation face the same types of barriers when attempting to access postsecondary education. These programs focus on bridging the gap between high school and postsecondary education, and also diminishing hurdles to college access. In order to diminish the effects of obstacles, college access programs were initially created to “lessen the educational disenfranchisement of underserved students by increasing college readiness and exposing underrepresented students to postsecondary educational opportunities” (Howard, 2016, p. 21). Each program, of course, has varying sets of approaches and strategies to reach this goal; however, the two most popular models are the student-centered model and the school-centered model. Funding for these programs can come from a variety of sources, but for the purposes of this paper we will focus on federally-funded and college/university-funded programs. (Dyce et al., 2013; Howard, 2016) College access programs can have many different effects on first-generation students. Depending on the intensity of the program, it could academically prepare students, increase their (K-12) school performance and on standardized tests (SAT/ACT), and can also increase students access and enrollment into postsecondary education. College access, first-generation students, and college access for first-generation students are all new and expanding topics of research. Currently there is not much published research on these topics, therefore there is much more research to be done.

College access is inequitable; minority and low-income students are at an extreme disadvantage to white and affluent students. In order to have a functioning democratic society, all citizens must have equitable access to a postsecondary education.

College access is an issue of equity. First-generation students frequently need support in attaining postsecondary credentials and college access programs are beneficial to these students. These programs can tremendously impact first-generation students’ lives by assisting their transition from high school and into a college or university.

My recommendations for improving college equity and access, in ways other than college access programs, are for states to impose more rigorous standards of learning, ensure that school systems have adequate funding, improve college affordability.

Understanding College Equity and Access for First-Generation Students

College access programs intentionally operate to combat the issue of inequity within the college matriculation process. Many of these programs are targeted towards first-generation students because these students are often underserved and possess limited access to postsecondary education. For first-generation students, financial status/class, race, gender, and cultural knowledge are enormous barriers when attempting to access a postsecondary education. Operating systems of oppression have caused many citizens to have been continuously disenfranchised and systematically excluded from higher education for generations–this exclusion resulted in the creation of the group known as first-generation students. (See Figure 1) College attendance rates have begun to rise over the past few decades, particularly among first-generation students, unfortunately, many of these students still struggle to transition from high school, into college, and out of college (Howard, 2016). An increasing number of students are interested in post-secondary education, but college enrollment rates have not been reflective of this. The disconnect between interest and enrollment rates show that many students aspire to attain a postsecondary education but are barred from accessing it. (Center for American Progress, 2009, 4) College access programs, however, are one solution used to mitigate this issue of access that first generation students face in their postsecondary education pursuits.

College Access is Inequitable

Being that minority and low-income students have been systematically disenfranchised for generations, they are at a large disadvantage to their white and affluent counterparts. White and affluent students have efficiently and effectively accessed higher education, which have led to generations of college educated people in these groups. In 2015, for example, while 32% of whites held at least a bachelor’s degree, only 22.5% and 15.5% of blacks and Hispanics, respectively, held the equivalent. (US Census Bureau, 2015) (See Figure 2) By looking at these statistics, we can determine that the effects of disenfranchisement are still occurring. First-generation students must combat these effects in order to enroll and complete their secondary education. (Kirst, Venezia, 2005; Howard, 2016) The gaps in college enrollment between white and affluent students and minority and low-income students continue to persist because of narrow approaches to address the range of obstacles to college access. (Hagerdon, Tierney, 2002) However, college access programs use myriad of approaches and strategies in order to address these barriers to access. (Perna, 2002)

Increased Access is Essential for Democracy

Increased college access will allow individual citizens to reap an assortment of benefits, such as “higher incomes and increased lifetime earnings, lower levels of unemployment and poverty, decreased reliance on public assistance programs, increased job satisfaction, greater likelihood of receiving employer-sponsored pensions and health insurance, healthier lifestyles, higher levels of civic engagement.” (2017 State of College Admissions, National Association of College Admissions Counseling, 4) In addition, providing citizens with high quality education is fundamentally democratic and, without doing so, structural inequalities will be perpetuated and barriers to education will persistently continue. (Friedman, 1982 75; Darling-Hammond, 2010, 25) “Education adequacy,” a term coined by the Century Foundation, is the belief that democracy is rooted in education; therefore, the ultimate purpose of education should be to “provide knowledge and skills sufficient to allow people to live fully…” (The Century Foundation, 2018) Democratic equality is known to be one of the three main goals of education. Since the U.S is a democratic society and we rely on the “political competencies of our fellow citizen,” it is extremely important that all students are prepared with “equal care to take on the full responsibilities of citizenship in a competent manner.” (Labaree, 1997, 42) By improving equity and access to postsecondary education, the United States will be able to “sustain its healthy democracy and high-stakes economy.” (Darling-Hammond, 2010) Therefore, in order to have a functioning democratic society, all citizens must have equitable access to a postsecondary education.

Purpose of the Paper

In this report, I examine the effects of college access programs on first-generation students. I layout my findings on obstacles first generation students face and focus on the expected outcomes of quality college access programs. I conclude that college access programs are a beneficial resource to first generation college students. To close, I include my thoughts on the areas in need of future research and my recommendations for improving college equity and access for first-generation students.

Previous Efforts to Increase Access

College access has been an issue for decades, and it is still prevalent today. Although there have been several attempts to diminish access gaps for certain groups, none of these attempts have been completely successful. The Higher Education Act, introduction of federal Pell grants, and the creation of community colleges were policies implemented in order to increase college access for students. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Higher Education Act (HEA). The act was passed to increase access to college for students from low socioeconomic families. Though the act did increase financial assistance students could receive to attend college, it did not increase the overall access all students had to college. (Camera, 2015) Although college attendance rates rapidly increased after the act passed, many students continue to struggle to access postsecondary education today. It was recently determined that the HEA was no longer effective with today’s college students. (Solomon, 2018) Therefore, the HEA is currently in the process of being reauthorized, in order to ensure that college is more affordable and accessible for all students. Federal Pell grants, similar to HEA, were introduced in order to diminish financial hardships on students enrolled in postsecondary education. Though these grants are often not substantial enough to cover the entirety of financial requirements expected from students, institutional grant aid is used to supplement student financial need. (Hurwitz, 2012) In more recent years, the budget for federal Pell grants have been increasing, therefore institutions have been forced to increase their grant aid and there has also been an increase on average student debt. (Hurwitz, 2012) (See Figure 3) For some students, community colleges have been a more affordable option for a postsecondary education. Although community colleges have been around since the 1850s, the number of institutions began to exponentially increase around the 1950s. (Geler, 2001) These institutions are praised for their work “increasing access to higher education, revamping developmental education for students arriving in college without college-level academic skills, and facilitating student movement through higher education and into the labor force.” (Doughtery, Larst, Marest, 2017) Although these institutions are often praised for increasing access for students, many of them are currently in need of reform. Many community colleges are often unaffordable, inefficient, and have poor credential completion rates. (Doughtery, Larst, Marest, 2017) The need for increased college access has been clear for decades, and the Higher Education Act, Pell grants, and community colleges all attempted to address this issue. Although these systems were unsuccessful, they did slightly improve college access. After these systems have been reformed, they will more adequately address the needs of first-generation students.

Review of Literature

Who Are First-Generation Students?

First-generation college students are an extremely diverse group that often struggle to access college. (Howard, 2016) The concept of first-generation students is very new and little research has been done on the group. Though there have always been “college students without college-going parents,” colleges and universities began to recognize first-generation students more often in the early 2000s (Wildhagen, 2015). Although there are a few definitions of first-generation students, a first-generation student is most commonly understood as either a student “for whom neither parent attended college” or “for whom neither parent attained a baccalaureate degree” (Bailey et al., 2013, p.3). Increasingly, researchers characterize first-generation students as students who do not have a parent who attended college. The number of first-generation students attending an institution will vary, depending on which definition is applied. For example, if first-generation students are defined as neither parent having attended college, then the population of first-generation students will most likely decrease (Bailey et al., 2013).

At this point, there are more first-generation students than non-first-generation students enrolled in postsecondary institutions (Davis, 2010). However, the data is often incomparable across institutions because of differing definitions. (Davis, 2010). Davis (2010) advocates for the explicit definitions of first-generation students, stating that this category should hold influence similar to that of ethnic minority status so that these underserved students earn extra opportunities for success through programming and other avenues. However, Wildhagen (2015) found that first-generation status may cause students to feel isolated. She warns that the vast diversity of this group could lead to the disempowerment of individualism for first-generation students, while Davis suggests diversity strengthens first-generation students as a whole and provides benefits to both the institution and the student. Though the group may be extremely diverse, often first-generation face the same types of barriers when attempting to access postsecondary education.

College Access Programs

College access programs are extremely pertinent in the stride to increase postsecondary access. These programs focus on bridging the gap between high school and postsecondary education, and also diminishing hurdles to college access. In order to diminish the effects of obstacles, college access programs were initially created to “lessen the educational disenfranchisement of underserved students by increasing college readiness and exposing underrepresented students to postsecondary educational opportunities” (Howard, 2016, p. 21). In the U.S, there are several types of college access programs. Most college access programs specific foci vary because of the diverse needs of local communities. Although there are many types of different college access programs, at the most basic level they each have the identical main goal to increase the number of disadvantaged students that enroll in college. Programs often focus on recruiting certain groups of students such as minorities or first-generation, but some programs are open to any student that wishes to enroll. Each program, of course, has a plethora of approaches and strategies to reach this goal; however, the two most popular models are the student-centered model and the school-centered model. Funding for these programs can come from a variety of sources, but we will focus on federally-funded and college/university-based programs. (Dyce et al., 2013; Howard, 2016)

Student-Centered Model

The student-centered model focuses on individual student growth and success through services such as college counseling, tutoring, and parental support (Howard, 2016). Programs that use the student-centered approach have more hands-on interaction with students such as “counseling, tutoring, mentoring, and workshops to provide students with information about the college admissions process as well as to provide assistance with obtaining financial aid […] and preparing for college entrance examinations.” (Engle, 2007) These programs are not used as the primary source of education for students, but “to supplement and extend a students’ weekday curricular and extracurricular experiences.” (Gullat, Jan, 2003) Many student-centered modeled programs are characterized by fostering a feeling of “sense of belonging and membership; a strong peer group; student initiated and directed projects and activities; frequent and regular contact with the same group of students over an extended period of time; opportunities to develop and master new skills; a strong sense of purpose; and opportunities for teamwork.” (Lieber, 2009) The Talent Search is a student-centered model that “focuses on information and college awareness for students in grades 6-12.” (Gullat, Jan, 2003) Similar to Upward Bound, a federally-funded college access program, the main goal of Talent Search is to expose middle and high school students to “college awareness and preparation.” (Engle, 2007) Although the student-centered model is most beneficial for some programs, other programs benefit more from using the school-centered model.

School-Centered Model

The school-centered approach is a framework that institutions use to create an “overall academic environment” to increase student success. (Howard, 2016, p.22) Since the school-centered model is costlier and more difficult to implement, the student-centered model programs are more popular (Howard, 2016). The school-centered model requires “faculty responsibilities [to] shift from a singular focus on academic instruction to more holistic instruction, coaching, and support that foster students’ learning, achievement, personal development, and postsecondary success.” (Lieber, 2009) Lieber (2009) identified four types of approaches programs can use to implement a school-centered model; each approach includes varying degrees of school faculty and staff involvement. Although the school-centered model requires a large amount of funding, training, and an implementation period, immersing students in a “college-readiness” school culture has proven to be beneficial for many students. (Lieber, 2009) One of the most popular examples of a school-centered approach to college access is GEAR UP. The program is a “school-based intervention” that uses a “‘blended’ school-centered and student-centered [approach to…] improve student performance within the environment of the school itself.” (Gullat, Jan, 2003; Engle, 2007) GEAR UP provides training, resources, and support for schools using the school-centered approach, instead of using the hands on student-centered approach like Upward Bound.

Federally-Funded Programs

Federally-funded programs often use both the student–centered model and school-centered approach. (Dyce et al., 2013; Howard, 2016) Federally-funded programs typically use the student-centered model. The TRIO program is a federal program created to “serve and assist low-income individuals, first-generation college students, and individuals with to progress through the academic pipeline from middle school to post baccalaureate programs.” (Department of Education, 2018) The federal program restricts which students can enroll in the program, by requiring that “two-thirds of students served by TRIO programs must come from families with income under $24,000.” (Tierney, Hagerdon, 2002) The initiative consists of eight separate programs, one being Upward Bound–which specifically seeks to increase college access for first-generation and low-income students. Upward Bound is typically institutionalized on college and university campuses, but the program continues to use the student-centered model. (Gullat, 2003) Many college/university-based college access programs also use the student-centered model.

College/University-Based Programs

Unlike Upward Bound, college/university-based programs are college access programs that are run and funded by a postsecondary institution rather than the federal government (Howard, 2016). Many college/university-based programs offer the incentive of earning college credits when enrolled in their program. The exposure to college-level courses increases students confidence and academic abilities to complete the rigorous coursework (Bailey, Karp, 2003) Although some college/university-based programs offer academic credit, many do not. One of the most beneficial aspects of college/university-based programs are their location. Generally, college/university-based programs are based on the institutions campus and allow students an early chance to gain hands-on experience on a real campus. Elon Academy is one example of a university-based program. Elon Academy exposes students to the culture of college and “prepares students and their families to meet the financial, academic, personal, and social challenges related to the transition to college.” (Parks et al., 2017, p.43)

Effects of College Access Programs

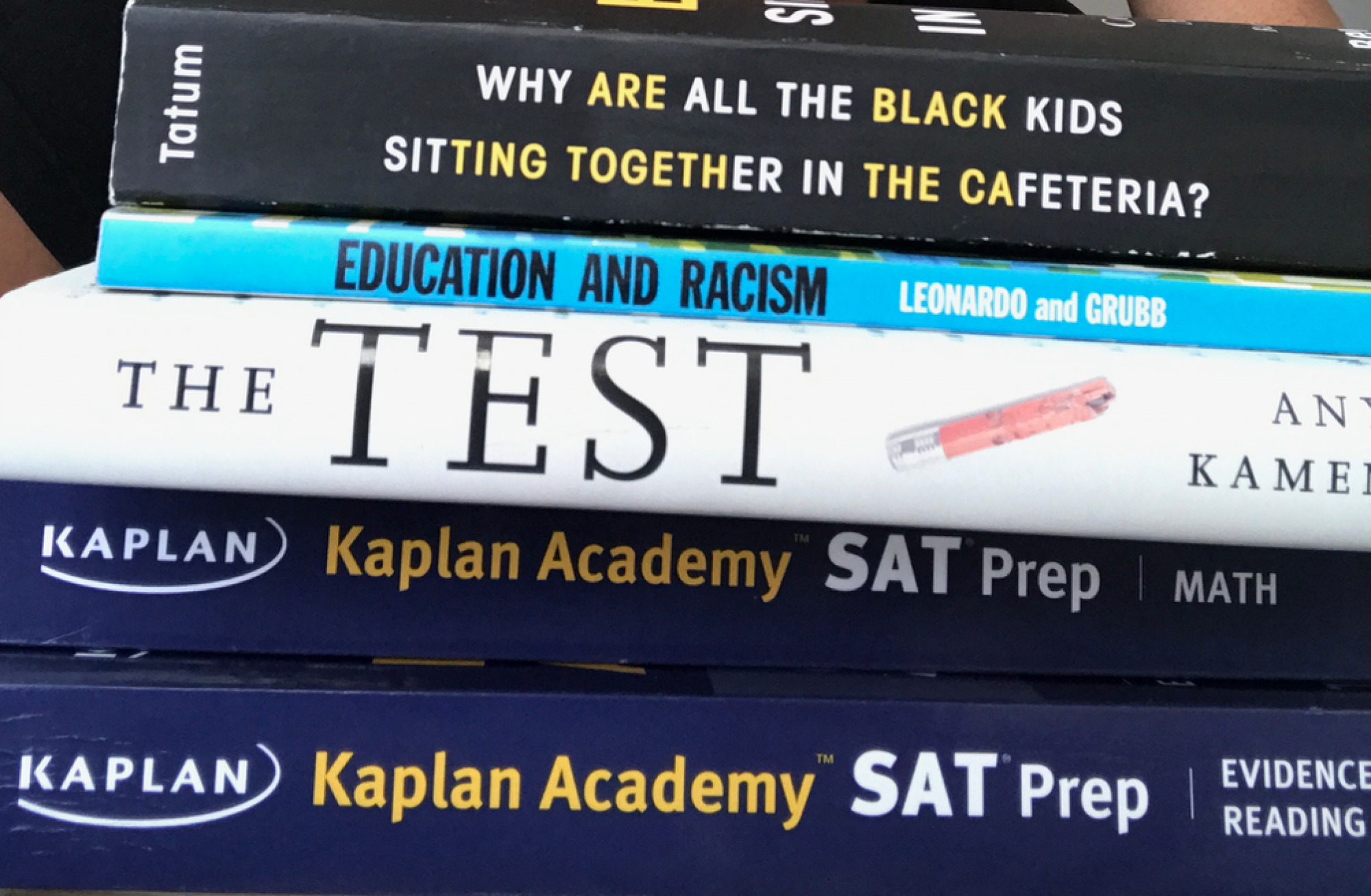

College access programs can have many different effects on first-generation students. Depending on the intensity of the program, it could academically prepare students, increase their (K-12) school performance and on standardized tests (SAT/ACT), and can also increase students access and enrollment into postsecondary education. However, a quality college access program would have all of the above effects, and even more impact, on the students.

Student Performance and Academics

Quality college access programs can strengthen students’ performance during their secondary and postsecondary education. Although college access programs main focus is to enroll students in college, it is important that students are maintaining their grades in secondary school so that they can be a competitive applicant. University-based and federally-funded college access programs can have a positive affect student performance. Breakthrough St. Paul has a student-centered model and is a non-profit organization. After being evaluated, Breakthrough St. Paul was deemed quite successful in both increasing students’ secondary academic performance and preparing students for postsecondary education. It was found that “94 percent of all BSP students and 100 percent of BSP high school students are enrolling and succeeding in honors courses […] BSP 9th graders passing an average of about two and a third honors courses a year.” (Swail, Quinn, Landis, Fung, 2011) Participants in another college access program, Education is Freedom, also saw impressive results while enrolled in the program. It was found that “students who participate in the program throughout high school are more likely to stay in high school and complete each grade, have higher GPAs, and take Advanced Placement classes.” (Swail, Quinn, Landis, Fung, 2011) Ensuring that students maintain, and even raise, their high school GPA and take a rigorous course-load plays an important role in students’ ability to access and enroll in postsecondary education.

Access/Enrollment to Postsecondary

Not all first-generation students are from low-income families, yet many college access programs are aimed at low-income youth who otherwise might not attend college (Dyce at al., 2012). Perna (2002) suggests the success of college access programs is determined by steadily increasing enrollment rates of program participants into a college or university. From a College Board survey, she deduced that successful college access programs focused on the specifics of enrollment discussed topics such as “predisposition to college,” “search for information about college,” and “choice of institution.” Successful college access programs recognize the importance of early interventions and exposure to the college application process.

Scholars find that college access programs increase the likelihood that a potential first-generation student follows through on their plan to gain a postsecondary education. Studies show that Upward Bound participants are more likely to “graduate from high school, attend a four-year college, and […] earn [on average] seven more credits in four-year colleges.” (Gullat, 2003) A study on GEAR UP, investigating its effects on postsecondary enrollment and persistence, found a positive correlation between time spent in the program and GPA (Ward et al., 2013). Overall, scholarship finds that college access programs increase high school achievement, acclimate students to the culture of college, and make students more comfortable and confident in their transitions.

Hurdles to College Access

First-generation students face a unique set of obstacles when attempting to gain access to postsecondary education. (Atherton, 2014, p.824) Many students face identical obstacles as their parents, and often continue the cycle by not accessing postsecondary education. To decrease this effect, researchers and academics have examined obstacles faced by first-generation students. The most prominent barriers are affordability and psychological obstacles/cultural disconnect.

Affordability

According to The College Board, college tuition and fees have exponentially climbed since 1971. (The College Board, 2017) (See Figure 4) In fact, the entire college application, matriculation, and graduation process are commonly known to be quite expensive. Students start the process by taking either the SAT or ACT because most colleges require these scores in order to apply. These tests both cost around sixty dollars, are usually taken outside of school hours, and are regularly at remote locations. (The College Board, 2018; ACT, 2018) To combat issues of cost, students that qualify for free/reduced lunch may receive a set amount of test waivers so that they are able to test for free. Some states, such as Kentucky and Arkansas, have made either the SAT or ACT a required assessment therefore, the states’ students are able to take the test at no cost and usually during school hours. (Kentucky Department of Education, 2018; Arkansas Department of Education, 2018) Next students have to fill out physical applications. Atherton (2014) asserts that because first-generation students often come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and homes with fewer resources, application fees can deter them from applying to college. (p.824) Thus, first-generation students are excluded from accessing college prior to the application process since they cannot afford application fees. (National Association of College Admissions Counseling, 2017)

After being accepted into a college or university, students (and parents) quickly realize that tuition and fees are not the only education-related expense the student will have. Room and board, books, supplies, and transportation are the main expenses of a college student. (The Lumina Foundation, p.4) Although most colleges/universities provide institution sponsored financial aid, too often students are forced to rely on loans, and/or apply for scholarships or grants. The cost for postsecondary education can quickly rack up, leaving students discouraged or extremely in debt. In College Affordability: Implications for College Opportunity, Perna (2006) acknowledges that family income “continues to be positively related” to college access and college choice, consequently we can assume that a family with limited family income may likely have limited access to college and college choice. Frequently affordability obstacles are portrayed as the “key” barrier to postsecondary education, however, cultural disconnect is another barrier in which first-generation students may encounter. (Kahlenburg, 2006; Wildhagen, 2015, p.295)

Culture

First-generation students may encounter psychological obstacles and/or cultural disconnect prior to enrolling and during enrollment. (Wildhagen, 2015). During the college application process, first-generation students may be very nervous depending on their level of unfamiliarity of the process. The students may doubt their academic abilities and may often require extra support during the process. (Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson, Covarrubias, 2012) Thinking ahead to their future, first-generation students may also begin to doubt their potential success in college. (David, 2010) Colleges, like all organizations, embody a unique culture that must be taught (Davis, 2010). More specifically, first-generation students must be taught to “[navigate] the bureaucratic organization of postsecondary institutions” (Davis, 2010, p.30). Regularly, first-generation students are unable to gain such cultural knowledge from family members and thus are deterred from or sometimes fail to complete the matriculation process. Though first-generation students are an extremely diverse group, much of the group consists of minority and low-income students. These groups all have a culture with which to affiliate—whether it be racial/ethnic culture, the culture of their socioeconomic status, or the culture of their home community, each group identifies with a certain culture. However, the most dominant culture in the U.S is white middle-class culture. (Yosso, 2005) White middle-class culture is most often recognized as the norm to be conformed to and is the culture on many college and university campuses. As students bring their own cultures to campus and are confronted with the “college culture,” they are forced to deal with “cultural mismatch.” (Stephens et. al, 2012) The mismatch occurs as the student realizes the disconnect between some of their own norms, values, and expectations, and their classmates’ whose cultural norms align with the white middle-class culture. (Stephens et. al, 2012) Adapting to college life and culture can be a large adjustment for many students, but the cultural clash can cause first-generation students to have an extended campus acclimation process. (David, 2010, p.59) A longer acclimation process can result in the student questioning their own cultural norms/practices, their college enrollment, and potentially slow the development of their identity as a college student. (David, 2010; Stephens et. al, 2012) As the students’ postsecondary journey continues, he or she may experience a “middle-position” in which they “straddle two cultures.” (David, 2010, p.59) As time goes on, the student may feel an “uncomfortable separation” from their home culture. (Hsaio, 1992) Cultural mismatch can have negative effects on first-generation college students, causing issues of access to extend beyond the college admissions process.

An Issue of Equity

College access is an issue of equity. Since all students are not afforded the same resources and knowledge about college and college culture, the “playing field” is unleveled. First-generation students frequently need support in attaining postsecondary credentials and college access programs are beneficial to these students. These programs can tremendously impact first-generation students’ lives by assisting their transition from high school and into a college or university.

First-generation students deserve creative and valuable college access programs to assist in their college application and entrance process; and although all students could benefit from college access programs, it is important that first-generation students are targeted. Though these students can successfully matriculate to and graduate from college without the assistance of college access programs, these programs can assist students by creating a smoother process. These programs are essential and positively impact first-generation college students. Although there isn’t much research and literature on the topic of first-generation students and college access programs, the current research is promising and provides the groundwork for future research.

Future Directions in Research

College access, first-generation students, and college access for first-generation students are all new and expanding topics of research. Currently there is not much published research on these topics, therefore there is much more research to be done.

College access is an issue that has affected many people in the U.S, and around the world. In order to increase college access, more research and analysis should be done. More research needs to be done on quality techniques for accessing college. As more research is done on effective college access techniques, more programs will be able to implement these techniques. Although there are a few case studies on college access, these case studies need to be performed in greater numbers. Frequent evaluations of students that participate in college access programs would be pertinent for future researchers to understand both the positive and negative effects of certain techniques. Therefore, the programs can be adjusted in order to increase “success.”

A standard and clear definition of ‘first-generation student’ needs to be determined, in order to increase uniformity and understanding. Currently, there are a few definitions of ‘first-generation student’ which can cause data to be skewed when attempting to calculate the number of first-generation students. (Bailey et al., 2013, p.3) After a uniform definition of first-generation students is established then postsecondary institutions and researchers can collect more robust and accurate data on first-generation students and offer a fuller, more comprehensive picture of the climate of postsecondary education for these students. Postsecondary institutions should begin collecting data on first-generation student attendance at their institutions, after ‘first-generation student’ is defined. First-generation students should be treated as a subgroup, in order to monitor changes within the group. As each institution collects data using the same parameters to define first-generation students, more research can likely be done about this specific category of students. Researchers will be able to more accurately describe the profile of first-generation college students within the United States. Since this group is quite diverse, it will be important to monitor and track subgroups (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, etc.) within the overall first-generation students group. In order for the research on this category to improve, the data surrounding the category must improve. Therefore, until there is a commitment to one definition of first-generation college students, it will be difficult for researchers to gather data and conduct comparable studies about the category of students.

In the future, research should focus on current college access programs and their impact on all students, but also specifically on different groups of students. It is important to monitor, evaluate, and analyze current programs, in order to find ways to improve them and to ensure that they are fulfilling their commitments to students. By disaggregating the data and studying the effects of college access programs, researchers and policymakers will be able to better understand gaps and where improvement is needed. The research should focus on all types of programs including federally-funded, privately-funded, college/university-based, student-centered, school-centered. Through increased research, new and innovative techniques may be discovered. These techniques could be implemented on a large scale, increasing college access for massive numbers of students.

Improving College Equity and Access for First-Generation Students

A quality college access program can help prepare first-generation students to survive college life academically, socially, economically, and psychologically. “Although providing access to college is a crucial first step, recruitment efforts alone are insufficient to ensure that first- generation students can take full advantage of the opportunity to attend college and to succeed there.” (Stephens et. al, 2012, p.1179) After becoming enrolled in postsecondary education, many first-generation students struggle both academically and socially. Transitioning into college is difficult, especially if the student is the first in their family to do so. Students may struggle with finding friends and family to talk with about this process, which can make the transition harder. (David, 2010) There are several ways to diminish the future chance of anxiety and struggle that comes with acclimation. In order to increase college access, access programs must address the variety of hurdles that bar first-generation students from attaining a postsecondary education. Often times, college access programs simply do not have the capacity to address the range of needs of enrolled students. Although college access programs have been proven to be effective, there are other ways to increase college access for first-generation students. My recommendations for improving college equity and access, in ways other than college access programs, are as follows:

- Impose more rigorous standards of learning. States should adopt rigorous standards for their primary and secondary schools, in an effort to prepare all students for college coursework. In order for first-generation students to be viable college candidates, they must have completed quality academic coursework. If students are not prepared academically, they will be unable to successfully graduate from the postsecondary institution. In addition, students who have completed rigorous coursework are more likely to enroll in a postsecondary education institution. (Tierney, Corwin, Colyar, 2005)

- Ensure that school systems have adequate funding. Inequitable funding to a school can cause a plethora of issues for first-generation students seeking postsecondary education. If a school has limited funding, it most likely will not have the resources needed to provide additional support to first generation students during their college application and matriculation process, including providing services such as college counseling/advising, and supplemental college preparation. (Judy, Noam, Schneider, 2014) Often times the schools with the neediest students extremely lack resources due to how school finance budgets are created through the combination of local, state, and federal tax dollar (School Funding: Do Poor Kids Get Their Fair Share? Urban Institute, 2017) However, there are a plethora of schools that have more than adequate funding. In these schools, the students may have access to these college preparation services, supplemental academic support, application and matriculation support, etc. Through inequitable school funding, by not providing services to the neediest students, inequity is perpetuated throughout the school system. This perpetuation creates a barrier for many students, especially first generation, often disabling them from even accessing the college application process. Adequate school funding is needed to provide students with appropriate and updated classroom materials and implementing high quality standards and assessments. (LaFortune, Rothstein, Schanzenbach, 2018)

- Improve college affordability. Affording college can be an extremely large barrier for first-generation students. Postsecondary institutions expensive tuition and fees often deter students from enrolling. Postsecondary education is expensive and often requires students to depend on private loans to pay for their education. Student loan debt can burden students for the rest of their lives. By making college more affordable for students, college access will increase. Without the burden or worry of making large payments or going into extreme debt, more first-generation students may enroll in a postsecondary education institution. (The Institute for College Access and Success, 2016) College affordability can be improved in ways such as increasing the amount of Pell grants that exist, improving institutions’ financial aid, and modifying loan interest rates. (Department of Education, 2016)

References

Atherton, M. C. (2014). Academic preparedness of first-generation college students: Different perspectives. Journal of College Student Development, 55(8), 824-829. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.georgetown.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1628062188?accountid=11091

Bailey, T. (2008). Beyond Traditional College: The role of Community Colleges, Career, and Technical Postsecondary Education in Preparing a Globally Competitive Work Force. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/beyond-traditional-college-global-workforce.pdf

Camera, L. (2015). A Right, Not a Luxury. US News. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/the-report/articles/2015/11/06/college-affordability-is-still-an-issue-today

Davis, J. (2010). First-generation Student Experience: Implications for Campus Practice, and Strategies for Improving Persistence and Success. Stylus Publishing, LLC. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017.Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/lib/georgetown/detail.action?docID=911903

Dougherty, K. J., Lahr, H., & Morest, V. S. (2017). Reforming the American Community College: Promising Changes and Their Challenges. Retrieved May, 2018, from Community College Research Center Teachers College, Columbia University website: https://ccrc.tc.columbia.edu/media/k2/attachments/reforming-american-community-college-promising-changes-challenges.pdf

Dyce, C.M., Albold, C., & Long, D. (2013). Moving From College Aspiration to Attainment: Learning From One College Access Program. The High School Journal, 96 (2), 152-165. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/article/497002/pdf

Engle, J. (2007). Postsecondary access and success for first-generation college students. American Academic, 3(1), 25-48.

Geller, Harold (2001). A Brief History of Community Colleges and a Personal View of SOme Issues (Open Admissions, Occupational Training and Leadership). Retrieved May, 2018. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED459881.pdf

Gullat, Yvette, &. Jan, Wendy (2003). How Do Pre-Collegiate Academic Outreach Programs Impact College-Going among Underrepresented Students? Pathways to College Networks. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.483.7094&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Kirst, Michael, & Venezia, Andrea (2005). Education Policy. 19(2) p.283-307 DOI: 10.1177/0895904804274054

Lafortune, J. (2018-04-01). School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement. American economic journal. Applied economics, 10(2), 1-26.doi:10.1257/app.20160567

Hagedorn, L. S., & Tierney, W. G. (2002). Increasing access to college: Extending possibilities for all students. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Howard, T. C., Flennaugh, T., and J. T. (2016). Expanding College Access for Urban Youth: What Schools and Colleges Can Do. New York, NY: Teachers College Press

Hurwitz, Michael (2012). The Impact of Institutional Grant Aid on College Choice. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(3), pp. 344 – 363 https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373712448957

Imbrenda, J. (2018). Developing academic literacy: Breakthroughs and barriers in a college-access intervention. Research in the Teaching of English, 52(3), 317-341. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.georgetown.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/2007453827?accountid=11091

Johnson, N. (2014). College Costs and Prices: Some Key Facts for Policymakers. Retrieved May, 2018, from https://www.luminafoundation.org/files/publications/issue_papers/College_Costs_and_Prices.pdf

Nagaoka, J., Roderick, M., & Coca, V. (2009). Barriers to College Attainment: Lessons from Chicago. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2009/01/27/5432/barriers-to-college-attainment-lessons-from-chicago

Parks, R., Parrish, J., & Holmes, M. (2017). Equity and access: Strengthening college gateway programs with credentials. College and University, 92(2), 43-46. Accessed on Dec. 21,2017. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.georgetown.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1922872037?accountid=11091

Perna, L. W. (2002). “Precollege Outreach Programs: Characteristics of Programs Serving Historically Underrepresented Groups of Students.” Journal of College Student Development, 43(1),64. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.georgetown.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/195176874?accountid=11091

Rose, Deondra. (2016) Studies in American Political Development. Cambridge. 30(1). p.62-93.

Salomon, Ken (2018). Will the Higher Education Act be Reauthorized in 2018? Thompson Coburn LLP. Retrieved May, 2018. https://www.thompsoncoburn.com/insights/publications/item/2018-03-02/will-the-higher-education-act-be-reauthorized-in-2018

Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S., & Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(6), 1178.

Tierney, W. G., Corwin, Z. B., & Colyar, J. E. (2005). Preparing for College: Nine Elements of Effective Outreach. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ward, N. L., Strambler, M. J., & Linke, L. H. (2013). Increasing educational attainment among urban minority youth: A model of university, school, and community partnerships. The Journal of Negro Education, 82(3), 312-325,356-358. Accessed on Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from http://proxy.library.georgetown.edu/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1462797598?accountid=11091

Wildhagen, T. (2015) Not Your Typical Student: The Social Construction of the ‘First-Generation’ College Student. Qualitative Sociology, 38, 285. Accessed on

Dec. 21, 2017. Retrieved from

https://doi-org.proxy.library.georgetown.edu/10.1007/s11133-015-9308-1

Appendix A

College Access Program- An outreach program created to in order to “lessen the educational disenfranchisement of underserved students by increasing college readiness and exposing underrepresented students to postsecondary educational opportunities” (Howard, 2016, p. 21)

Cultural Mismatch- The mismatch between cultures, that occurs as the student realizes the disconnect between some of their own norms, values, and expectations, and their classmates’ whose cultural norms align with the white middle-class culture. (Stephens et. al, 2012)

Federally-Funded Program- A college access program that is funded and run by the federal government. (Howard, 2016)

First Generation Student- A student “for whom neither parent attended college.” (Bailey et al., 2013, p.3)

School-Centered Model- A framework that institutions use to create an “overall academic environment” to increase student success. (Howard, 2016, p.22)

Student-Centered Model- An approach used by college access programs, that prioritizes a focus on individual student growth and success through services such as college counseling, tutoring, and parental support (Howard, 2016).

College/University-Based Program- A college access program that is funded, organized, and run by a college or university. (Howard, 2016)

Appendix B

Figure 1. Percentage of Persons with Bachelor’s Degree or More in 2015. Reproduced from data retrieved from U.S Census Bureau, 2015.

Figure 2. Undergraduate Enrollment in Postsecondary Institutions, Fall 2000-2015. Graph retrieved from National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cha.asp#info

Figure 3. Average Tuition and Fees for Private 4-Year, Public 4-Year and Public 2-Year Institutions. Reproduced from data retrieved from The College Board. https://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing

Figure 4. Cumulative Debt of Bachelor’s Degree Recipients in 2012 Dollars. Table retrieved from The College Board. https://trends.collegeboard.org/student-aid/figures-tables/cumulative-debt-bachelors-recipients-sector-time