The Effects of a Discriminatory Dress Code Policy:

A Case Study of Mystic Valley Regional Charter School

Jaida Harris

Introduction

“Schools both serve and are part of communities…” (Leonardo and Grubb, 2014, 55). The quality of school relationships with community members depends upon how schools treat, teach, and police students; communicate with parents; and interact with community businesses and organizations. Often schools with high rates of minority students foster a negative school-community relationship because they expect their students of color to assimilate to the White, middle-class culture. By perpetuating this idea, a deficit view of minority cultures and student groups is created and sustained (Yosso, 2005).

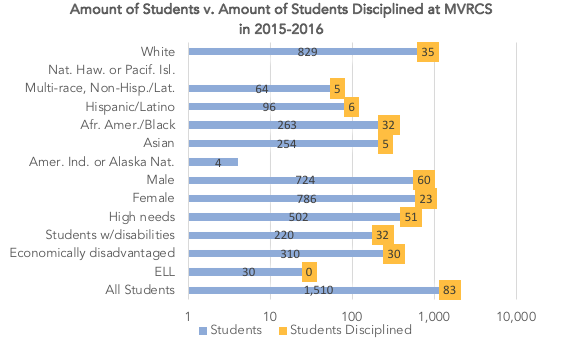

Mystic Valley Regional Charter School (MVRCS) is located in Malden, Massachusetts just north of Boston. Around 1500 students currently attend the school with 43% being minority. Within the school population, 25% of students are economically disadvantaged. Although half of the school’s population consists of minority students, only one black teacher/staffer works in the school (“AG tells Malden charter school hair rules are biased”, 2017). Students are required to wear uniforms, and the school withholds a strict dress code policy.

Purpose and Problem

This post examines the questions, ‘in what ways does MVRCS dress code policies perpetuate racism?’ and, ‘how do these dress code policies and their implementation affect parent-administration, student-student, student-administration relationships?’ This study includes background information on dress code policies and the dress code policy controversy at Mystic Valley Regional Charter School. I explain the ways sexism and racism are upheld in the school’s dress code policies; how these policies affect both intra-school relations and school-community relations. Lastly, I address how the idea of white supremacy can be withheld through these policies.

Policy and Case Background

Although dress code policies are written to regulate student dress, they regularly target specific groups of students. The MVRCS dress code policy limits the ways in which black students can wear their natural hair. Most black people’s hair grows out or up, and by limiting hair height and thickness to two inches, black students are targeted. Common Afrocentric hairstyles, such as afros and twist outs, cannot be worn. The hair of black students who choose to wear their hair naturally, is often in a state that exceeds two inches. MVRCS even has a rule on hair extensions. The rule pertaining to extensions are more so directed, and enforced, towards the black female population. It is common for black females to wear extensions in their hair, whether it is for braids or to give the appearance of longer hair. Braids and hair extensions are not only for style, but are often also worn to help protect hair from heat and chemical damage. These particular rules restrict the hairstyles in which black male and female students can wear their natural hair, without the use of chemicals.

During the 2016-2017 school year at Mystic Valley Regional Charter School, several black and biracial students were punished for violating school dress code. Students are punished with detentions, suspensions, or bans from extracurricular activities. The problem does not lie with black/biracial students being punished, but that they were punished more frequently and harshly than their white counterparts because of the way the policies are written. After their twin daughters were repeatedly penalized, two parents decided to challenge the school’s dress code policy. Maya and Deana, black female students, were repeatedly written up for wearing braids in their hair. The braids violated the school dress code that prohibits hair extensions. The girls were unable to attend prom or participate in athletic events because of their repeated violation of the school’s dress code policy.

Analysis

The MVRCS dress code policy perpetuates racism and, subsequently, promotes white supremacy. The dress code policy clearly demeans and discourages the representation of black hair culture within the school. By blatantly targeting hairstyles typically worn by black students, the policies force students to dismiss their own culture in order to ascribe to WASP culture.

“It helps provide commonality, structure, and equity to an ethnically and economically diverse student body while eliminating distractions caused by vast socioeconomic differences and competition over fashion, style, or materialism,” – (Letter from MVRCS Board of Trustees, 2017)

The keywords in the above quote are ‘commonality’ and ‘structure’. The use of ‘commonality’ and ‘structure’ imply that there is a norm in which the students must adhere to. This norm is the school culture, which as we know, is white Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) culture. However, WASP culture being the ‘common’ standard and epitome of ‘structure’ perpetuates the idea of white supremacy. WASP culture being the culture that students must ascribe to, preserves the idea that white culture is the superior culture. As the school’s administration promotes these ideas of ‘commonality’ and ‘structure’, they are upholding the idea that the only acceptable culture is WASP culture, which in turn maintains white supremacy.

The implementation of discriminatory dress code policy specifically negatively affects parent-administration, student-student, and student-administration relationships. Unequal policing of minority students on dress code policy will cause division within the school and students’ parents and administration. Students of color will recognize disparities between how they are policed and punished differently from their white counterparts. This blatant inequality will most likely cause resentment and strife between students of color and white students. MVRCS boasts a “Non-Discrimination Policy” stating that the school “does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, age, sex, gender identity, homelessness, religion, national origin, disability or sexual orientation with regard to admission, access to programs or activities, or employment opportunities” (MVRCS Website, 2017). However, it can be argued that the school does discriminate against certain groups—students of color (black/biracial students through the hair policy), female students (over extensive hair policy), and homeless students (Dress code states that students must be clean shaven/no facial hair) (MVRCS Dress Code Policy, 2017). Minority families may feel increasingly uncomfortable with sending their students to MVRCS because it doesn’t seem to be upholding the values that they advertise. Leonardo and Grubb (2014) explore the ways in which schools “deculturalize” minority students (71). They acknowledge that “students of color are not appreciated for their cultural specificity” (Leonardo and Grubb, 2014, 71). Examples of this unappreciation can be seen throughout MVRCS’s dress code policy. The school seeks to maintain “commonality” between all of the students, which upholds the idea of cultural unappreciation (MVRCS Letter from Board of Trustees, 2017). This commonality results in the “stripping” of students’ culture. Bourdieu argues that WASP culture can become so normalized in our institutions that it eventually becomes “common sense culture” (Leonardo and Grubb, 2014, 63). Since WASP culture is the dominant culture in the United States, it is often perpetuated and maintained unconsciously. This subtle perpetuation, however, explains the maintenance of institutional racism (Leonardo and Grubb, 2014, 64). Through the preservation of the ‘common sense culture’, WASP culture remains dominant while minority cultures are suppressed. White supremacy is reinforced while black culture is suppressed, while WASP culture is considered the standard of ‘commonality’ and ‘structure’, black students are forced to “[assimilate] into Eurocentrism” (Leonardo and Grubb, 2014, 58).

Conclusion

Currently, MVRCS’s discriminatory dress code policy is still in effect. Although the dress code policy is in place to simply regulate student dress, MVRCS’s policy overtly targets black female students. By forcing these students to conform to WASP norms, minority students are subconsciously being told that their culture is inferior to WASP culture.

Reference List

- Banks, James A. (2010). Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives Seventh Edition. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1986). The Forms of Capital. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, p. 241-258.

- Hardbach, Meredith Johnson (2016). Sexualization, Sex Discrimination, and Public School Dress Codes School Inequality: Challenges and Solutions, Allen Chair Issue 2016: School Discipline Policies. University of Richmond Law Review, 50, 1039-1063.

· Lazar, Kay (2017). AG tells Malden charter school hair rules are biased. Boston Globe, 149. Retrieved from https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2017/05/19/attorney-general-orders-malden-charter-school-stop-punishing-black-students-for-hairstyles/V1JDcutCmhDISlpk97KdEM/story.html?p1=Article_Related_Box_Article

- Leonardo, Zeus, & Grubb, W. Norton. (2014). Education and Racism: A Primer on Issues and

- Dilemmas. New York: Routledge.

- Mattler, Katie (2017). Black girls at Mass. school win freedom to wear hair braid extensions. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/05/22/black-girls-at-mass-school-win-freedom-to-wear-hair-braid-extensions/?utm_term=.ca8634216ca0

- Mystic Valley Regional Charter School Board of Trustees (2017). Letter regarding school uniform policy. Retrieved from http://www.mvrcs.com/ourpages/auto/2017/5/22/59042933/Letter%20to%20MVRCS%20Community.pdf

- Mystic Valley Regional Charter School Parent/Student Handbook. Retrieved from http://www.mvrcs.com/pdf/2016-2017%20Student%20Parent%20Handbook.pdf

- Mystic Valley Regional Charter School Website. Retrieved from http://www.mvrcs.com/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=248980&type=d

- Yosso, Tara J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 69–91.