The Effects of Singularly-Focused Test-Based Accountability Systems

Laura Gervater and Jaida Harris

Georgetown University

April 2018

In recent decades, standards-based reform has become the ‘de facto national education policy’ (Schwartz & Robinson, 2000), and ever since the era of No Child Left Behind, test-based accountability has therefore received too much emphasis in education Working on the core assumption that schools were either unable or unwilling to push for drastic student improvement, and that harsh accountability policies could spur the necessary change, this singular focus on standardized test scores has continued to plague schools since 2001 (Marsh, Pane, & Hamilton, 2006).

Yet, no test can hope to capture everything a student knows or paint student achievement in the proper context. We know that a wide variety of factors can affect student performance, including health, test anxiety, or cultural background knowledge (Dukor, guest lecture). Standardized tests are incomplete measures of school quality, and many researchers and policymakers recognize that they are often not an accurate measure of student achievement (Schneider, 2017). Yet, they form the cornerstone of most accountability systems, and poor performance on these tests can therefore lead to dire consequences for schools and for individual students.

The preeminence of test-based accountability has had myriad negative effects on schools. As the case of Rosemont High School exemplifies, this fixation has taken away focus from instructional improvement and promoted excessive focus on academic scores rather than student development and relationship-building. As a result, the overall quality of students’ education diminishes significantly. As the case study of Rosemont High illustrates, schools are trapped between conflicting modes of accountability: accountability in terms of scores and keeping the doors open versus accountability to deep learning and real student advancement. This problem of conflicting accountabilities strikes not only Rosemont, but also schools across the nation (Firestone & Shipps, 2005).

Test-Based Accountability Takes Focus Away from Instructional Improvement

Amid a national craze about proficiency cut scores, it’s easy for schools to lose sight of real, lasting learning. Because standardized tests usually require finding a ‘right’ predetermined answer to narrowly defined questions – rather than testing higher-order thinking skills (Turnipseed & Darling-Hammond, 2015), these regimes at best narrow schooling to a reading and math-focused curriculum with lessons comprised of rote memorization and by-the-book test prep strategies. At worst, it actively incentivizes schools to cheat (Koretz, 2017). Whether from cheating or inflation due to targeted test prep, standardized test scores can go up without producing corresponding increases in students’ actual knowledge (Shepard, 2000). Therefore, standardized tests are not the gold standard for providing accurate reflections of student learning.

Equally importantly, standardized tests often do not clearly present teachers with a path to for helping students move forward. If teachers are too focused on standardized tests, they cannot properly implement formative assessments – assessment for learning – which is what would truly help teachers understand where students are and create a plan for progress (Duckor & Perlstein, 2014; Stiggins, 2005). Though ESSA allows for some decrease in focus on standardized tests by promoting use of alternate school quality indicators, test scores still reign supreme.

Rosemont High School is a prime example of such a system’s negative effects. The school’s principal strives to build a ‘strong climate of learning’ by going beyond standardized assessment data and tailoring instruction with data from both summative and formative assessments. She has focused on developing protocols – a key aspect of developing strong school culture (McDonald, Mohr, Dichter, & McDonald, 2003) – that improve results for children. However, the Greater Oakdale Unified School District’s ‘Scorecard’ accountability system did not account for any of this. Instead, the system focuses on standardized test scores and gave the school a D on Academic Status – student proficiency – and an F on Academic Progress – change in scores; these marks accounted for 70 percent of the final score. Additionally, the Scorecard did not reflect the fact that 11th grade reading scores on the state exam rose from 38% scoring at proficiency to 50% or that many of the students at the school ultimately went on to become first generation college students. In short, the Scorecard provided an extremely limited and heavily test-focused perspective on learning at Rosemont High. The resulting low scores result in intense pressure for the school, which is threatened by the prospect of school closures and competition for student enrollment. Because of these potential sanctions, the stakes are so high that several principals in the district even feel compelled to ‘game’ the system by targeting interventions at specific ‘bubble students’ rather than devoting energy to improving instruction for everyone.

These Systems Cause Hyperfocus on Scores At the Expense of Other Factors

Effective leaders, collaborative teachers, involved families, and supportive environment are all factors that contribute to positive outcomes for children (Schneider, 2017). However, the standardized test obsession causes accountability systems to deemphasize these factors and instead focus excessively on academics. For instance, drastic sanctions such as school closures or reconstitutions are often based on ‘academic achievement’ as measured by standardized test scores. If school leaders live in constant fear of these outcomes, they may lose their broader focus on good teaching and good learning environment. Yet, especially for students who are traditionally underserved and may struggle in school, it is critically important to create an environment full of care (Noddings, 2005) and Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Test-based accountability does not account for or incentivize either of these steps. It does not incentivize building relationships. It does not reward schools like Rosemont that encourage first generation students to reach for college. It does not allow for celebration of creativity, which will be a critical skill in the modern workforce (Turnipseed & Darling-Hammond, 2015). The focus on accountability simply crowds these things out and diminishes their value.

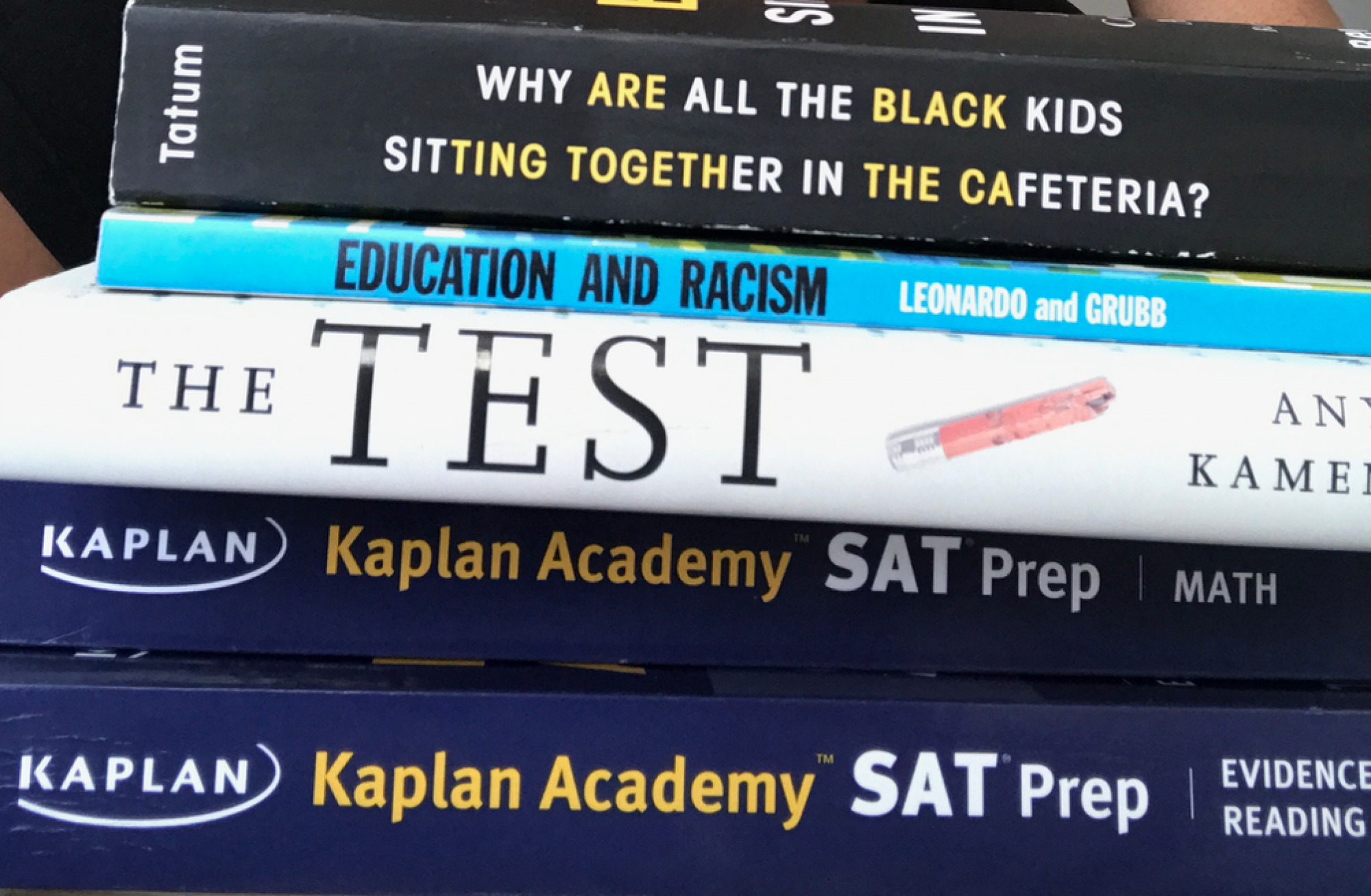

Rosemont High scored an A for School Climate thanks to the principal’s emphasis on creating a positive school culture. Yet, overall, its grade on the Scorecard averaged out to a C+ because of standardized test marks. For district officials unfamiliar with the particularities of Rosemont, or for parents choosing a school for their children, the Scorecard does not paint a nuanced picture of the school’s positive climate and data-driven efforts to foster academic improvement. Instead, they see a school grade that is nearly 70% failing. While Rosemont certainly needs to improve academically, especially in terms of ACT scores, the Scorecard does not show the improvement it has already achieved. In a context where school choice is increasing, this could significantly affect Rosemont’s enrollment and its future overall. Further, by allowing standardized tests to comprise 70% of the Scorecard points (see Figure 1), the district is conveying the message that test results are more important than creating a positive environment, having solid protocols and professional culture, encouraging students to go to college, and developing relationships with families and teachers; this does not make for a multifaceted, quality education.

What Can Be Done

First, to provide a more complete academic picture, accountability systems should include academic components other than standardized tests. Figure 2 shows the critical importance of measurement selection; on Greater Oakdale Unified’s Scorecard, Rosemont High scored a 0% based on its ACT proficiency. However, using the ACT as the sole indicator of ‘academic performance’ ignores that 50% of students were proficient on the 11th grade reading exam; this makes academics at Rosemont High seem significantly worse than they truly are. At the bare minimum, using a wider variety of tests would provide multiple reference points; ideally, accountability systems would utilize other academic measures such as portfolios or projects that can showcase student learning beyond test-taking. A wider variety of measures would provide a more helpful perspective on students’ true abilities (Supovitz & Klein, 2003). Further, if the district decides to implement the more expanded measure of academic progress, it should disaggregate the data by subgroups (racial/ethnic groups, students with disabilities, etc.) in order to ensure a focus on equity.

To ensure success within this system, a school leader could also implement a system of interim self evaluations for the school. The Rosemont principal recognized that “good teaching is what really matters for school quality.” If school leaders establish their rubric of good teaching and constantly provide feedback and coaching, they will be able to improve practice and identify needs for improvement (Antoniou et. al, 2016); this, in turn, will help students learn more and help the school improve its test scores for the annual district evaluation. To maximize the usefulness of the self evaluation, school leaders must ensure to conduct the evaluation several times a year, using criteria that will align with the district’s annual evaluation.

Most of all, we note that many educational researchers argue that accountability systems should include a variety of metrics that cannot be easily measured by standardized tests (Rothstein, 2006). In a truly equitable accountability system that paints a rich, multidimensional picture of students and schools in terms of culture and achievement, excellence is no defined exclusively by students’ standardized test scores. In order to convey that the district values more than test scores alone, and in order to provide parents with a more complete picture of a school, scorecards should highlight non-test-based measures such as positive climate, family relationships, socioemotional learning, purposeful lesson planning, and a variety of other elements that together make up a truly great education.

Figure 2: Rosemont High Scores on ACT vs State Reading Exam Paint Different Pictures

Sources

Antoniou, P., Myburgh-Louw, J., & Gronn, P. (2016). School self-evaluation for school improvement: Examining the measuring properties of the LEAD surveys. Australian Journal of Education, 60(3), 191-210.

Duckor, B., & Perlstein, D. (2014). Assessing Habits of Mind: Teaching to the Test at Central Park East Secondary School. Teachers College Record, 116, 020301 (2014). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Firestone, W. A., & Shipps, D. (2005). How do leaders interpret conflicting accountabilities to improve student learning? In W. A. Firestone & C. Riehl (Eds.), A new agenda for research in educational leadership (pp. 81–100). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Koretz, D. (2015). Adapting Educational Measurement to the Demands of Test-Based Accountability. Measurement (Mahwah, N.J.), 13(1),1-25.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American educational research journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Marsh, J. A., Pane, J. F., & Hamilton, L. S. (2006). Making sense of data-driven decision making in education. RAND Corporation. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/content/dam/ rand/pubs/occasional_papers/2006/RAND_OP170.pdf

Mathis, W. J. (2015) School Accountability, Multiple Measures and Inspectorates in a Post-NCLB World. National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from: http://nepc.colorado.edu/files/publications/Mathis%20RBOPM-1_0.pdf

McDonald, J. P., Mohr, N., Dichter, A., & McDonald, E. C. (2003). The power of protocols: An educator’s guide to better practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Noddings, N. (2015). The Challenge to Care in Schools, 2nd Editon. Teachers College Press.

Schwartz, R. B. & Robinson, M. A. (2000). Goals 2000 and the Standards Movement. Brookings Papers on Education Policy 2000, 173-206. Brookings Institution Press.

Shepard, L. (2000). The Role of Assessment in a Learning Culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4-14. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1176145

Stiggins, R. (2005). From Formative Assessment to Assessment for Learning: A Path to Success in Standards-Based Schools. The Phi Delta Kappan, 87(4), 324-328.

Supovitz, J. A., & Klein, V. (2003). Mapping a course for improved student learning: How innovative schools systematically use student performance data to guide improvement. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.